The Flu Pandemic of 1918 in Kassa (Kosice), 1918

Veronika Szeghy-Gayer, one of the research fellows of our institute, has recently published a short article on the local impact of the 1918 flu epidemic in Kosice of present-day Slovakia that was officially called Kassa in the latter part of 1918. Here, we publish the English translation of the original piece that first appeared in Slovakian on the site of the Slovak Academy of Sciences.

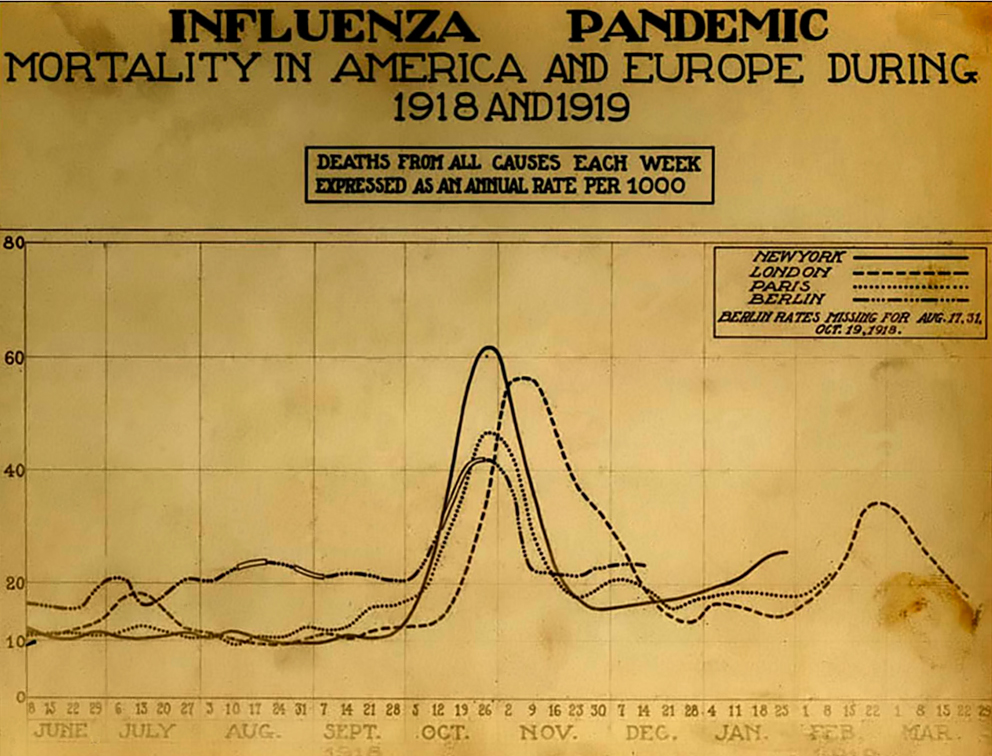

The so-called Spanish Flu that ravaged the world more than a hundred years ago was one of the most devastating diseases in the history of humanity. It killed more people than World War 1. What was the experience of the epidemic in Kassa like and how did officeholders respond?

During the autumn of 1918, the political-administrative leaders of Kassa were busy with trying to tackle conflicts that arose from soldiers returning from the frontline and from the shortage of supplies. In the meantime, the spread of the flu epidemic was also becoming worrisome. „everyone gets it and everyone suffers from it except for those that die within the first 24 hours“ – wrote one of the correspondents of the daily called Kassai Hírlap. When the medical officer, Géza Nagy (1869–1922) reported nearly 2000 illnesses on 30 September, the mayor, Béla Blanár, declared that there was an epidemic and formed a committee for tackling it on the same day.

Measures

The measures that the town leaders introduced sound familiar today. The mayor ordered all schools to close already in September. (Elementary schools and high schools only opened in the new state in early 1919) In the second half of October, film theatres, theatres, sports events, and dance parties were banned. The dance schools had to stop, too. Regulations regarding restaurants and cafes were less rigid than they are in the current epidemic. These could stay open, but between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. and between 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. they had to carry out disinfection, and during these hours customers were not allowed in. Factories had to disinfect and airing between noon and 2 p.m. The windows of streetcars had to be kept open. Residents were advised to stay away from strolling and mass visits to cemeteries, churches and other sites of prayer. Those houses where a sick person stayed had to be designated with red tags.

Based on decrees of the Ministry of the Interior, the town hall also ordered that pharmacies should stay open until 10 pm and supply medicine to those that needed it even beyond that hour. The Ministry of Defence ordered army surgeons to provide care to civilians. On 19 October there were only 13 cases of death caused by the epidemic, however, ten days later this number went up to 40. Political meetings and celebrations held in the wake of the Aster Revolution, as well as the gathering groups of customers in front of bakeries and butchers, certainly facilitated the spread of the flu.

Numbers

Although there have not been systematic research into the number of victims, based on the official papers of the medical officer of the town and the dailies that regularly published reports about the sessions of the committee trying to deal with the epidemic, one may quote a few figures. We learn from the reports of Géza Nagy medical officer that in September and October 1918 there were 47 deaths caused by the virus and between 20 November and 28 November, there were a further 15, therefore, a total of 62. He put the number of illnesses at 2000 on 30 September, 1584 in October and 604 between 20 and 28 November. From other statements of his, we also know that on average there were 40-50 new cases daily in November. If we accept these, then we reach a total of 4200 cases in autumn 1918 that is about 7% of the residents when we add up the 40-44 000 citizens and the army stationed.

Remarkably, the virus was most deadly for those aged between 14 and 35 and it killed quickly. This feature frightened the people. According to date from late November, 70% of the citizens were under 40 years old. Since the epidemic quickly spread among the soldiers, the town and the army command signed an agreement according to which those that fall ill from the virus were to be treated and isolated in the army hospital on Raktár Street (today: Skladná, Kasarne Kulturpark). Contemporary experts said that the epidemic was lighter in Kassa than in other parts of Hungary. According to these opinions, the first wave of the disease, which started in early 1918, killed relatively few people compared to the second wave of October and November. The third wave killed more than the first, but far less than the second one, in Spring 1919. If the general trends applied to Kassa, we should put the number of dead at as high as 120-150 and the number of illnesses at 5-6000.

Contemporary fake-news

It was a widespread belief that brothels were responsible for spreading the disease among soldiers. Those involved in the sale of liquor advocated that alcohol was the best protection against the virus.

Celebrity victims

We can count the King of Hungary, Margit Kaffka, the Hungarian writer (and her little son), Guillaume Apollinaire the French poet, and Max Weber (1864–1920) among the victims. Looking at the local scale, we need to mention Pál Halmi, a member of the renowned family of lawyers from Kassa, who died at the age of 38 and was a war veteran in Budapest.

According to historian Harald Salfellner the number of the victims of the Spanish flu epidemic was between 46 000 and 77 000 in the territory of Czechia. We may accept the estimate that the number of those that died from the virus in the territory of present-day Slovakia was half of that number, yet we must stress that there have been no systematic research projects on the question.

Sources

Kassa Város Levéltára, fond Úradného hlavného lekára v Košiciach, 1827–1940

Kassa Város Levéltára, fond Magistrátu mesta Košice, 1239–1922

Kassai Hírlap, 1918. szeptember-december

Felsőmagyarország, 1918. szeptember-december

Harald Salfellner, Die Spanische Grippe. Eine Geschichte der Pandemie von 1918. Prag Vitalis Verlag 2018, 168 p.

Veronika Szeghy-Gayer, Civilek elleni erőszak Kassán: Az első csehszlovák megszállás hónapjai (1918. december-1919. június) [Violence against civilians in Kassa: The first months of occupation (December 1918 – June 1919). In: Müller, Rolf; Takács, Tibor; Tulipán, Éva (eds.), Terror 1918-1919 : Forradalmárok, ellenforradalmárok, megszállók. Budapest Jaffa Kiadó 2019) pp. 53-83.