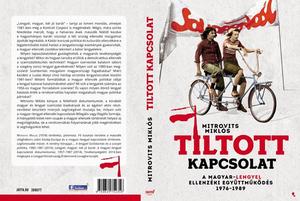

Forbidden Relationship - Opposition in Poland and Hungary 1976-1989

Based on available archival documents, contemporary samizdat literature and interviews with the actors of the time, Miklós Mitrovits’s new book discusses the semi-legal and illegal forms of contact between the Polish and the Hungarian opposition movement. This volume sheds new light on the Hungarian opposition, moreover, it helps to understand the process of systemic change, thus, it fills a gap in historical knowledge.

“A Polish and a Hungarian are good friends” – goes the saying that also appeared in the lyrics of a song by Kontroll Csoport, the short-lived, but ground-breaking underground music band that voiced criticism in the early 1980s. Yet, the fact that it was the opposition movements of the two countries that cherished this traditional friendship starting from the second half of the 1970s has nearly faded into oblivion. The book posits that events in Poland constituted the most important external impact on the cultural and political opposition in Hungary. The Hungarian opposition looked at the brave Poles with admiration.

What were the experiences that enriched the activities of the Hungarians? How did the democratic opposition learn techniques for creating samizdat publications and content

? How did they organize a summer camp for poor Polish children at Lake Balaton? How was the Solidarity movement received in Hungary? Why the satirical weekly called Ludas Matyi launch a defamatory campaign against the Poles in 1981? How did the objectives of the Hungarian opposition change after the military grabbed power in Poland? What consequences did Poles draw from the revolution of 1956? How did Polish examples influence the political parties in Hungary at the time of systemic change?

Major topics that the book covers:

· Polish and Hungarian opposition established contact with each other in 1976 in Paris on the occasion of a conference organized for commemorating the 20th anniversary of the revolutionary events in Hungary and Poland. It was there that Adam Michnik, one of the leading figures of the Polish opposition put forward the program of the so-called new evolutionism that served as a compass for those that willed the end of the state socialist political system.

· In 1978, the Hungarian democratic opposition organized illegal free universities, based on the Polish blueprint. Discussing the way events unfolded in Poland were among the key elements of the syllabus. Along with three other Hungarians, Sándor Szilágyi, the person in charge of such courses, took part in the strikes at the shipyards of Gdansk and in the formation of the trade union called Solidarity.

· The first Hungarian samizdat journals appeared while Solidarity was active and mostly discussed the developments in Poland. In late 1981, Gábor Demszky used Polish institutions as a model when he founded the AB Independent Publishing, which was the first independent publishing house in Hungary.

· Sándor Csóri, the leading figure of the so-called „people's movement” participated at a mass rally in Cracow, where Lech Wałęsa gave a speech. Csoóri and his party asked a question about the 1956 revolution in Hungary. When the question was read out the crowd cheered loudly. Csoóri wrote a poem about this experience.

· In the summer of 1981, the Foundation Supporting Poor People hosted Polish children that came from underprivileged background at the location called Kékkő near Lake Balaton. Police kept harassing the holidaying children and „definitively” banned Wojciech Maziarski, the Polish student acting as interpreter, from Hungary. In 1982 Hungarian authorities prevented the event from taking place again. Despite this, there were so many contributors that a railway wagon could be filled with goods and sent as aid to Poland.

· The emergency declared in Poland brought about a new situation for the Hungarian opposition, too. This triggered the first serious discussion about the future of the system. The forum for this was Beszélő, a samizdat journal.

· On the second anniversary of the formation of Solidarity, 30 August 1982, there was a protest demonstration at the statute of Bem. Organizers were arrested and the call to Polish could not be read out. Tibor Pákh improvised a speech in which he called on those present to pray in order to point out members of the secret service. They could be revealed because they did not pray.

· In June 1986, intellectuals including Csaba Gy. Kiss, István Kovács, Sándor Csoóri and Árpád Göncz prepared a Festschrift volume for the 70th birthday of professor Wacław Felczak. A year later, the Gábor Bethlen Foundation gave awarded its literary prize to Zbigniew Herbertnek. It was Sándor Csoóri who read out the praise.

· Within the Socialist Block, the first memorial stone dedicated to the revolution of 1956 in Hungary was unveiled in Podkowa Leśna, near Warsaw in October 1986. The events of the Hungarian revolution were widely commemorated in Poland and a dozen samizdat appeared and posters and stamps designed for the occasion.

· In 1987, it was his experience in Poland that motivated Zsolt Keszthelyi to refuse military service even at the cost of imprisonment. In Poland, there were a series of demonstrations of solidarity where participants demanded his release. In the autumn, there was a hunger strike at Bydgoszcz with the same purpose.

· During the same year, students of the István Bibó Student Mentorship Program, including Viktor Orbán and László Kövér, visited Poland several times. On their first visit, they took part in the pilgrimage of John Paul II in Gdańsk. At that time the police arrested their hosts. During a later visit, they participated in a conference that the opposition organized about disarmament. Later, a follow-up event took place in Budapest.

· In February 1989, the Hungarian-Polish Solidarity group was established in Podkowa Leśna. The organization launched a bilingual journal and initiated several actions. Members celebrated national holidays of both nations and supported each other during the months of systemic change.

· During the year, Poles were present at national meetings of the Magyar Demokrata Fórum, at the reburial ceremony of Imre Nagy and at the first legal celebration of 23 October. Members of the Hungarian opposition eagerly followed the roundtable discussions that began in Poland and were intent on learning from these.

For the table of contents please visit: https://www.academia.edu/42084823/Tiltott_kapcsolat._A_magyar-lengyel_ellenzeki_egyuttmukodes_1976-1989

The book may be ordered at https://jaffa.hu/tiltott-kapcsolat-1415

Links between dissenting groups in Hungary and Poland I. Flying University and Samizdat

Links between dissenting groups in Hungary and Poland II. – Emergency in Poland and the opposition in Hungary

Miklós Mitrovits (1978) is a Historian and Polonist. He is a senior research fellow at the Institute for Central European Studies, József Eötvös Centre at the University of Public Service and at the Centre for the Humanities in Budapest. His main fields of expertise are post-World War II Central Europe and the history of Hungarian-Polish relations. His key academic publications are A remény hónapjai… A lengyel Szolidaritás és a szovjet politika, 1980–1981 [Months of Hope....Polish Solidarity and Soviet Politics 1980-1981 (2010), Lengyel, magyar, két jó barát. A magyar–lengyel kapcsolatok dokumentumai, 1957–1987 [Poles and Hungarians are like friends. Docuements of Polish-Hungarian Relations, 1957-1987] (2014). In recognition of his efforts, he received the Cross of Knights Honour of the Republic of Poland in 2014.