Everyone was shocked

On 4 June 2020, the head of our institute, Pál Hatos, gave an interview to alfahir.hu about questions of the Trianon Treaty. The questions discussed were mainly related to the foreign policy options of Hungarian politicians and the life of Hungarians in the successor states.

Before the Trianon Treaty, Hungary was a multi-ethnic state. What were the demographic and ethnic patterns in spatial terms?

The last census of the pre-partition Hungarian Kingdom took place in 1910. According to this, the proportion of Hungarians had increased compared to the previous 50 years and it reached 54% if we exclude Croatia. This growth was largely due to the assimilation of Germans and Jews. While towns featured proportionally more Hungarians, this growth was not so straightforward in the countryside. In Transylvania, especially in the Transylvanian Plain (Mezőség), Romanians, and in the Uplands (Felvidék) Slovaks “overtook” hundreds of villages. The first step was a change in terms of the languages spoken. Overall, Hungary was a multi-ethnic country with a slight Hungarian majority, at the time when the world war broke out. While assimilation of Germans and Jews seemed unproblematic (Jews in Hungary had no national identity anyway), it was much more complex in the case of other nationalities. Some of the Slovaks undoubtedly took up Hungarian identity, another part, especially in the Eastern part of the Uplands, they became majority in territories that had previously belonged to the Hungarian or the Ruthenian ethnic zone. The policy of assimilation failed among the Serbs of Southern Hungary and among Romanians of the so-called Partium (north-eastern and eastern counties attached to Transylvania in the 16th century) and of Transylvania.

Was it true of the national leaders, too?

It might sound surprising but members of national elites were well versed in Hungarian culture. Unfortunately, this was not reciprocal. Neither István Tisza nor Oszkár Jászi spoke Romanian even if Albert Apponyi was good in Slovak. (The latter had unique talents for languages.) Romanian, Slovak and Serbian national leaders all spoke Hungarian as fluently as if they had been native speakers. They could quote Hungarian poets. However, this knowledge did not bring them closer to Hungarians. The effect was rather the opposite.

From the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, they were increasingly hostile to the Dualist establishment of Hungary, although they did not voice a clear agenda for secession.

They emphasized the grievances and the lack of political rights, or they turned to the reform plans of Franz Ferdinand, the royal heir that did not sympathize with Hungarians. The military defeat in World War 1 was a precondition for the idea of secession to take hold. It was similarly important that towards the end of the war – and not during its first phases! – Great Powers decided to partition Austria-Hungary. It is true that there was discrimination, paternalism and state violence on behalf of Hungarians. Clearly, external powers encouraged initiatives and a more radical agenda. We know that the Kingdom of Romania backed Romanians in Hungary just as Serbia backed the Serbs and Russian propaganda was actively present among Ruthenians. Yet, until late in the war the situation was nowhere near to civil war despite occasional clashes that claimed lives.

What was the foreign policy situation like for Hungary? What were the attitudes?

There was no independent foreign policy since the dualist structure of Austria-Hungary this was one of the domains that were to be managed in “common”. It proved fatal that this common foreign policy was increasingly single-minded towards the German alliance. This is how Hungary entered the war as part of the Central Powers. For instance, there was not a system of mutual guarantees in place with some of the formal allies, such as Italy or Romania. It was Mihály Károlyi – who was considered a nationalist at the time – that tried to approach Russia in order to balance out German dominance in continental Europe. However, this move did not bring any results. There were a number of illusions about foreign policy in Hungary. The lack of space for an independent foreign policy, and the unjustified sense of security that arose from this, were important among the causes of the Trianon treaty.

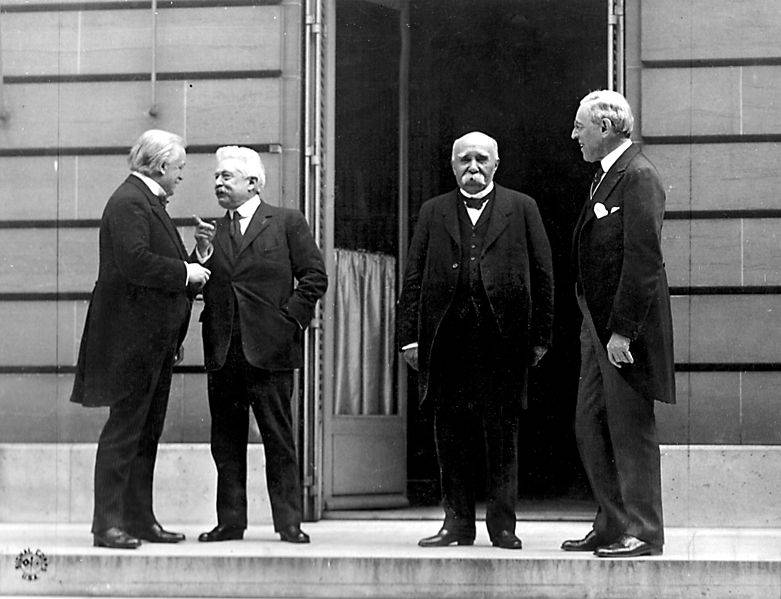

The “Big Four”: Lloyd George, Orlando, Clemenceau and Wilson

What was the Hungarian policy towards nationalities? Was it hostile or did it try to adjust to demands?

The law that regulated the rights of nationalities after the compromise of 1867 was the creation of the great generation of the Reform Era. This law granted ample space in the realms of culture and education, however, posited that there is only one political nation and that is the Hungarian. In the age of nationalism, formal cultural rights did not satisfy nationalities. Ethnic leaders demanded that nationalities should be recognized as political entities. However, the gravest issue was that Hungarian governments drifted away from the concept that József Eötvös and Ferenc Deák laid down in the law of 1868. They believed that becoming Hungarian was the only way ahead for nationalities. However, it is an exaggeration to say that there was whole-scale oppression on the basis of nationality in Hungary. If there had been such a severe oppression, the proportion of nationalities could not have grown in the regions mentioned above. It is a fact, however, that the list of grievances that Romanian and Slovak intellectuals could present abroad was growing. They presented their case quite successfully. Although there was no rift until World War 1, the Hungarian elite did not recognize the issues and did not respond in a timely manner. Shortly before the war, István Tisza initiated a meeting with representatives of Romanians in Hungary, which eventually did not take place. These negotiations could have hardly succeeded since Tisza wanted to offer only seats in the parliament and more positions in local administration.

Even though the masses were apolitical or indifferent, it was easy to represent social misery, material and cultural deprivation as if these were ethnic problems. In many villages that had Romanian or Slovak majority population, the landowner was Hungarian. One could have pointed out stables and domestic animals that the landowner possessed as the result of Hungarian exploitation. So the plan to apply both nationalism and liberalism for the creating a unified nation out of multiethnic conditions, failed in Hungary, unlike in France in the early 19th century. This is so even if we have to stress that, at the turn of the 19th and 20th century, people that belonged to ethnic minorities could carry on with their daily life, unharmed.

What were the forms that the propaganda that ethnic minorities exhibited abroad took? How did this propaganda impact the Hungarian polity?

From the turn of the century on, there were a growing number of reports directed to foreign audiences that talked of Hungarian lords oppressing nationalities. These met with sympathy, especially in France and Great Britain. Géza Jeszenszky [a renowned Hungarian conservative politician] wrote an excellent monographic study on the reasons and extent to which Hungary lost its standing in the eyes of British public. In much of the 19th century, Hungary was seen as the nation of Kossuth and the champion of liberty, however, due to the efficient political propaganda that Seton-Watson and his associates exhibited, from around 1900, Hungary appeared as an oppressor. Importantly, this bad image was not limited to states with opposing interests. German public also had an unfavourable view on Hungarians. László Ravasz, who would become an influential protestant bishop and public figure, noted that his professors in Berlin associated Hungarians, in an anti-Semitic vein, with Jews and with Eastern barbarians in the early 1900s. The change in the image of Hungary was clear, but Hungary did not take notice of it, unfortunately. However, all this would not have been sufficient to bring historic Hungary to an end if Austria-Hungary as a state had not been in danger.

Although the political salience of Slovak and Romanian intellectuals living in emigration grew during the war, Woodrow Wilson’s famous declaration did not go beyond the right to national self-determination.

So when did nationalities present their demand for secession/partition?

As late as the spring of 1918. At that time, it became clear for entente powers that Austria-Hungary would not ask for peace without Germany and that it did not have sufficient influence over Germany to convince the latter that it was time for negotiations. The Czechoslovak emigré government gained recognition in the summer of 1918. However, it is not so well-known that the USA endorsed Romanian claims regarding Transylvania only days before the truce on the Western front. We have to keep in mind that Romania was initially an ally of the Central Powers and left them, attacking Hungary in 1916, just like Italy one year earlier. Central Powers rebuffed the attack relatively soon and even occupied Bucharest, forcing Romania to sign a peace treaty in the spring of 1918. This, theoretically, annulled the agreement that Romania had with the entente including territorial claims and promises. However, when Austria-Hungary was falling apart at the end of World War 1, French and British politicians chose to disregard this circumstance out of geopolitical considerations. It is important to emphasize that it was not at all obvious from the start that successor states would be allowed to annex large areas from Hungary and Austria. This decision was made quite late into the war.

Did this decision surprise Hungarian politicians? Did they expect loss of territory?

There were fears and there was anxiety but for the public losses were unexpected and hit rapidly. For example, István Apáthy, who was an internationally renowned zoologist and a committed patriot, wrote that it became clear only in the autumn of 1918 that the road to independent Hungary leads to the grave of historic Hungary. The Hungarian political opposition, which had the support of the majority of Hungarians, believed that the marriage with Austria was an unhappy one. It wanted independent Hungary but they linked this independence to territorial integrity and disregarded the advice that Ferenc Deák gave fifty years earlier, according to which such a configuration was not viable.

It took Mihály Károlyi, Sándor Wekerle and even István Tisza unaware when the Romanian army was permitted to reach the River Tisza.

Trianon did not occur in 1920. On 4 June, signatories only confirmed a de facto situation that was already in place. The army of Austria-Hungary collapsed so that, starting from autumn 1918, there was nothing that would stop Romanians, Serbs and Czechs from advancing. Serbians occupied the Southern Lands (Délvidék), Újvidék (Novi Sad), Szabadka (Subotica) and even Pécs and Baja [the latter two remained in Hungary, eventually] Then, during Christmas which was an unhappy one for Hungarians, the otherwise badly equipped Romanian troops marched into Kolozsvár (Cluj). Around New Year’s Eve, Czechoslovak rule began in Kassa (Kosice) and Pozsony (Bratislava). The only direction from which no danger was coming was Austria. It is not so well-known that the area that we call Burgenland today was Western Hungary under actual Hungarian control until the autumn of 1921.

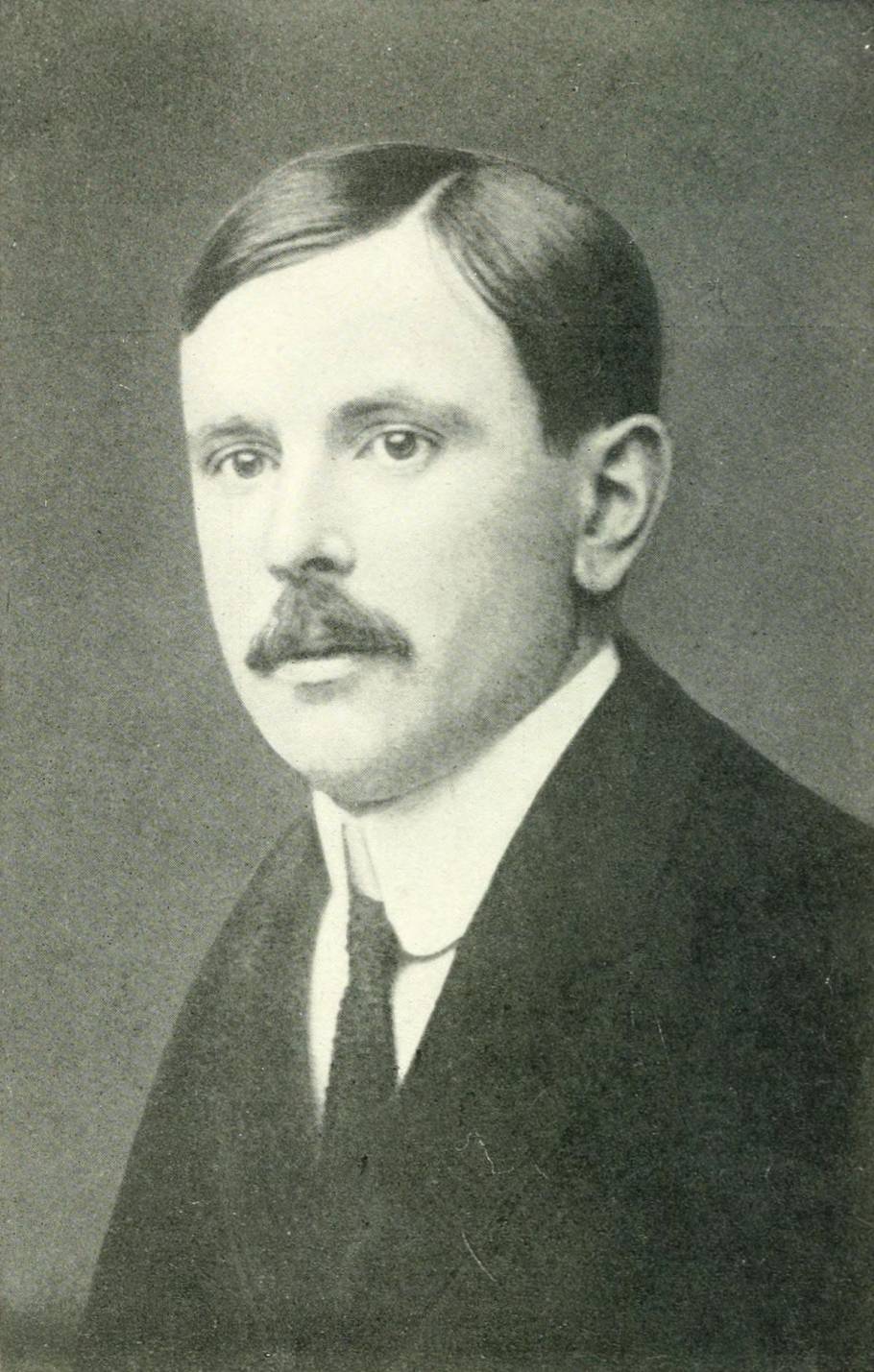

Robert William Seton-Watson, one of the leading figures in propaganda against Hungary

In the autumn of 1918, there was a significant turn in internal politics. How did Mihály Károlyi’s government react to hostile armies marching ahead?

There was not a single Hungarian government that acknowledged territorial loss in those years. Although Mihály Károlyi came to power with the Revolution of Aspen, during his unfortunate four-and-a half-month-long rule, he never made any remarks that indicated that he would accept the loss of an area.

He believed in a pacifist dream that had its roots in the realization of the impact of the world war: 660 000 Hungarians soldiers died in vain. He also saw that only a third of the military retreated from the frontlines to Hungary in an organized manner, so that Hungarian soldiers would not be able and willing to continue fighting. Even the units that kept to military order did so only because territories they had to pass through, proved hostile. This was true of Austrian, Slovenian, and Croatians lands.

There was chaos in autumn 1918 and this was accompanied by a naive politics. There were no military preparations even though there were instances of armed self-defence. The most spectacular and heroic example of this is the Szekler Army (Székely Hadosztály), but we have to note that it numbered only 8 000 during its best days. Yet, they held out and kept their positions near the area of Csucsa (Ciucea) in Kolozs (Cluj) County from January 1919 until April 1919.

The Soviet Republic of Hungary was declared in March 1919 and the Red Army was no pacifist.

The communist turn took place on 21 March 1919 when Béla Kun took control. Neither the left-leaning no ther right-leaning historiography likes to articulate that this was in the middle of panic.

Mihály Károlyi was not willing to acknowledge the Vix-protocol that included that Romania would annex even more territory. He opted for “Eastern orientation”. He believed that the victorious troops of a world revolution would protect Hungary from the imperialism of successor states. This is to say that a national hope was part of the communist takeover. We may quote the renowned contemporary author, Ferenc Herczeg who expected that the Bolshevik regime would be of “a type with solid backbone” that “will save us from a situation where we only own those parts of our country that Slovaks and Romanians do not want to take.” Of course, this quickly faded. It is true that it was only the Bolshevik government that launched armed actions in order to recapture territories among the de facto Hungarian governments of the time. Initially, these actions were successful. Under the command of Aurél Stromfeld, a former colonel of the staff of Austria-Hungary who served with merit throughout the world war, Hungarian troops reached the Polish border. They captured Kassa and Eperjes (Presov) in the northeast and Érsekújvár (Nové Zámky) and Selmecbánya (Banska Stiavnica) in to the west. The newly installed regional heads of Czechoslovak administration considered that they might have to evacuate Pozsony (Bratislava). However, when the French premier issued an ultimatum, Béla Kun, the communist leader, turned to revolutionary illusions once again and thought that if he obeyed the conditions, Romanians would retreat from the Trans-Tisza region. When the entente did not keep its promises, Kun ordered armed action for liberating the area, however, this expedition was badly organized and quickly collapsed.

The Romanian counter-attack reached Budapest. What are the details that we know?

It is not common knowledge that it was not Miklós Horthy or the National Army that overthrew communism. It was the actions of Romanian troops that brought an end to the Soviet Republic of Hungary. The length of the time period that the Romanian army spent in the Great Plains was twice of the length of communist rule in Budapest. According to contemporary estimates, the Romanian occupation caused seven times larger damage as Bolshevik rule. Despite this, in historiography, the emphasis is mostly on the actions of Bolshevism. However, new results on the Romanian rule are coming up soon. It is clear that Romanian troops systematically robbed households in the Great Plains. This explains why was it that while Horthy’s National Army had serious issues with recruitment, the Red Army recruited 2000 people in two hours for its campaign against the Romanian army in the town of Szentes in Southern Hungary.

Mihály Károly and the Szekler Army

It was the next government that had to conclude peace treaty negotiations.

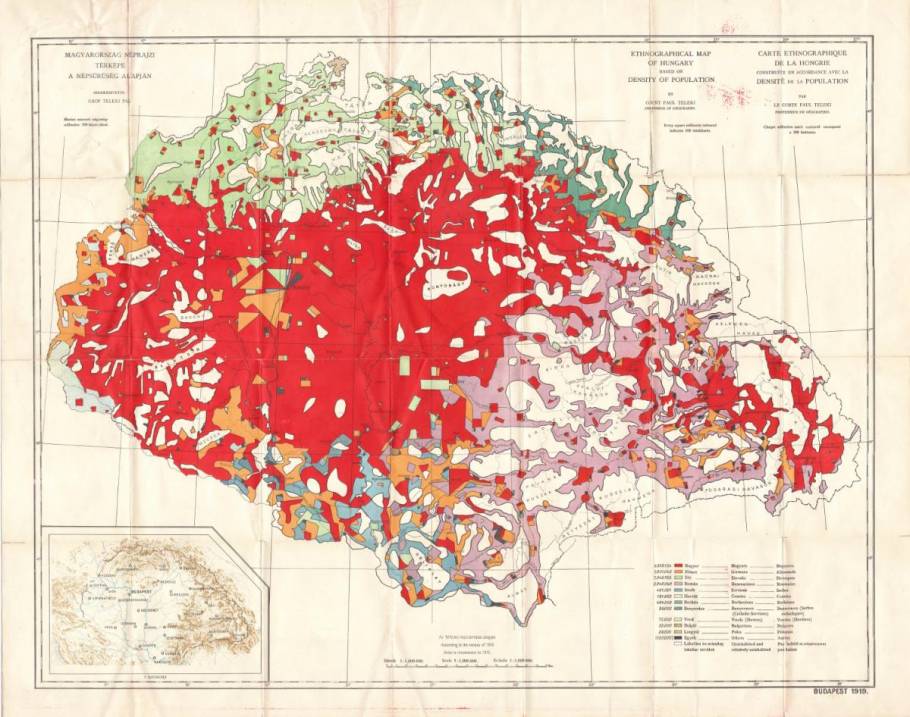

It is widely known that Albert Apponyi gave a great presentation in French language in January 1920 and Pál Teleki and his colleagues prepared comprehensive data and maps for the negotiations. However, by then, the decision about boundaries had been. Actually, it was made in the first months of 1919.

So, Bolshevik rule did not really make the prospects worse. During the negotiations at Versailles, the borderline was modified in favour of Austria in order to convince the latter that it was better not to join Germany.

Albert Apponyi, Pál Teleki and István Bethlen came up with a geography- and history-centred argument trying to resist against the injustice that was in the making. Some historians say that if they had been more diplomatic and had dropped the idea of St. Stephen’s Hungary they would have gained territorial concessions with British support. It might or might not have worked, we shall never know. It is important to note, however, that it was clear for the delegation that it was not possible to keep the entire territory even with Croatia excluded. Yet, they claimed the opposite in public.

The reason for why it is very difficult for Hungarians to get over the loss is because they do not find an audience for their complaints. Apart from Hungary, 1918-20 had a positive message for nearly all nations. The list includes Poland that was partitioned and wiped out in the late 18th century and revived in 1918. It was in those years that the Baltic states became independent. And of course, Romanians, Czechs and Slovaks celebrate the period that produced Greater Romania and Czechoslovakia.

Could Hungarian diplomacy have said no to the treaty? Was there an option for veto?

It was not really an option, although both Teleki and Apponyi considered it. István Bethlen knew that there was no other way and that veto could have made things worse. After four and a half years of destructive war and after the quasi civil war that followed there was need for reconstruct the country. There was famine, rationing, and there was a general shortage of materials, including coal and wood. Indeed, blockade was the major obstacle for both the Károlyi- and the Kun-government. No fat, food and coal were coming in. Without these, railways could not operate and it was not possible to heat the houses. So without signing the treaty, more famine was to come and there was no point of taking further risk. Thus, signing the treaty was a responsible decision.

In Hungary, society and politics did not come to terms with the conditions forced upon them. How far did it influence foreign policy during the Horthy-era?

Revision of the Trianon treaty and the injustice it meant was the major goal of Hungarian politics in the interwar period. It proved tragic that the partial revision that was realized was not the outcome of a European agreement. Instead, it took place with Hitler’s and Mussolini’s assistance. There were some important side-effects of the review of borders. For example, Slovakia became independent for the first time and it could keep Pozsony (Bratislava) as its capital. Also, taking back the sub-Carpathian region in the northeast meant that there was a border with Poland and tens of thousands of Polish came across it when Germany attacked Poland in September 1939. The corridor towards Székelyföld (Szeklerland) ran through areas with Romanian majority population. It is important to recall that Hungarian politics made steps that led to murder and were also suicidal: anti-Jewish legislation was implemented in Transylvania, and the sub-Carpathian region where Jews constituted a significant portion of the Hungarian population. Many of them, those that could, sought refuge in Romania in spring of 1944. This is part of the Trianon-problem, too.

The right to national self-determination was among the Wilsonian principles. How far multi-ethnic successor states respected these regulations?

The peace treaties signed at Versailles had important clauses that aimed to protect minorities. However, these were no so comprehensive as Wilson would have liked them to be. Eventually, the USA did not sign the treaties, thus they left the peace system. The clauses provided some means of protection for Hungarians living as minority, but there were differences to the extent to which they were implemented. Czechoslovakia respected them, while Romania did so to a lesser extent. However, it was an important feature of those times that all successor states attempted to undermine the Hungarian middle classes and communities materially via interference with property ownership patterns. Overall, the clauses did not guarantee an appropriate cultural and national life for the Hungarian minorities in the successor states.

Between 1920 and 1945, those that lived in the partitioned territories did not give up the hope that the previous setting would return. Then, the six-year-long “Little Hungarian Realm” reassured identities for the next decades. This was so even if during the interwar period, the Hungarian public living in the successor states was significantly more left-leaning than the public in Hungary, and that the arrogant, intolerant attitude of civil servants posted to Transylvania often triggered disappointment even among Hungarians. In the autumn of 1940, there were instances of ethnically motivated mass murders and atrocities that the Hungarian military committed and Hungarian authorities did not even attempt to negotiate with Romanian politicians in Transylvania, they were simply repatriated. Sándor Márai, an outstanding contemporary writer, defined the period as a paradox: a gift from fate. For him, it meant the recapture of his hometown from where, subsequently, the family of his wife was deported to Auschwitz, along with the Jews that lived in the town.

The famous ‘red map’ of Pál Teleki

How did the left-leaning views of Hungarians in minority manifest?

My argument is not that most of them were leftists, but there were periodicals and organizations in which socialist or even communist influence was tangible. We may think of the journal Korunk in Kolozsvár or the Sarló movement in Czechoslovakia. Particularly in Czechoslovakia, the general atmosphere and political culture was more democratic than in Hungary. In contemporary Hungary, it was inconceivable that the governing party might fall out of power even though there were elections. We also have to realize that many of those that were involved in the leftist regimes of 1918-1919 took refuge in Transylvania or in the Uplands (Felvidék) and lived there, and some of them became involved in politics, too.

Some currently relevant questions: is revision of the treaty a realistic scenario, and can we see autonomy as a realistic goal?

I believe that we have to struggle for autonomy because that is the only idea and practice that would not only lead to a mental appeasement of Hungarians but that may be recommended internationally in any multi-ethnic context. If that becomes reality, Hungarians will have the scope for a comprehensive cultural and national life. Revising Trianon through military means is out of question.