Colectiv - Alexander Nanau’s documentary and its context

On 30 October 2015, a deadly fire broke out at a club called Colectiv in Bucharest. It killed 60 people on the site and injured more than 160. The reason behind the high number of casualties were the crowd inside, the insulation made of inflammable material, the small number of extinguishers and emergency exits, thus disregard for safety regulations. Just like at Club West Balkan in Budapest four years earlier, this negligence claimed lives.

The incident at Colectiv triggered much stronger reactions in the Romanian public, however. Voices did not only demand punishment for the owners of the club but urged structural changes almost immediately. When the irregularities and the controversial role of authorities came to light, the initial shock turned into anger. Participants at protest demonstrations stressed the responsibility of public authorities and demanded measures against corruption that were omnipresent in Romania. Many people quickly made a link between factors such as misfunctioning institutions that did not ensure that safety regulations were adhered to, that victims received proper care, and the chaotic mode institutions functioned. As a result of protests, Victor Ponta, the Prime Minister who headed a coalition with waning popularity and was personally discredited in a plagiarism case, resigned in a couple of days. Dacian Ciolos’s government replaced him, which was said to be one of non-political experts. However, the case did not end there. Although the minister for health care stated that there was no need to transport patients to hospitals in Western Europe because the quality of care in Romania was on par with what one could receive in Germany, a number of survivors passed away. With the passage of time, even those died who did not suffer life-threatening injuries in the fire. This triggered the second wave of the scandal in the spring of 2016. A team of journalists working for the sports daily, Gazeta Sporturilor, found out that the reason for the infections that caused deaths was a chain of fraud with disinfectants.

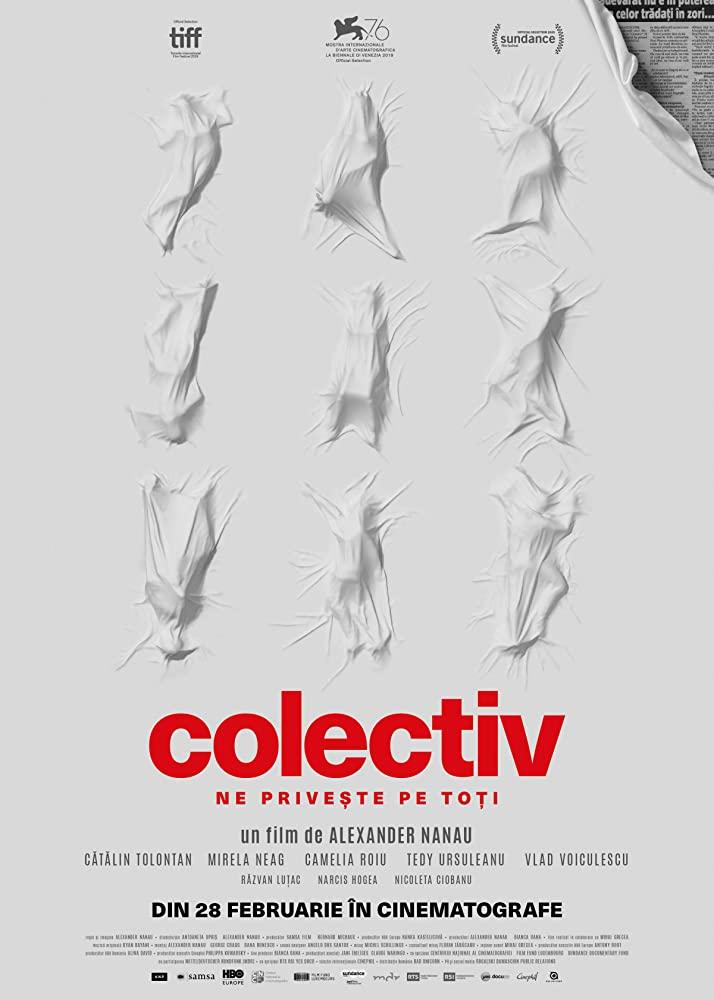

The theme of Alexander Nanau’s 109-minute-long documentary is the investigation and interconnected cases of corruption. The film Colectiv was released in 2019. In the opening scenes, we see excerpts of newscasts and from videos recorded with mobile phones showing the fire, the panic and the rescue operation. After these shocking scenes, and beyond the drama of survivors and relatives, stories of investigation and of bureaucratic struggle unfold. Although the director does not neglect the memory of victims and the suffering of survivors, problems of the Romanian health care system and the contradictory mode authorities operate occupy the centre stage.

The documentary runs along three parallel lines. The work of journalists of Gazeta Sporturilor – Cătălin Tolontan and his colleagues – constitute the first one. They were the ones that reconstructed the details of the circumstances of the death of those that suffered less than life-threatening injuries. After an investigation that resembles a thriller, they established that a foreign vendor supplied diluted disinfectants to hospitals and that these significantly contributed to the spread of infection that eventually killed several survivors of the fire.

The second line is made up of the personal stories of survivors and relatives: the pain and effort of a young woman who tries to continue her life and the way the family of a young male victim copes with grief. Nanau tells these in low key and reveals shocking details and emotions without exaggeration. Finally, the third line is about the struggles of two ministers of health of the Ciolos-government. The first one had to resign as a result of the scandal related to disinfectants. The second one had a background as an activist and embarked on a hopeless battle against the rotting and corrupt structure of the health care system in a ministry where “90% of the staff was incompetent.” The young minister wanted a thorough investigation into the causes of infection and improve conditions, but he quickly learned his boundaries. He had to realize that he was nearly unable to act against the groups that wished to maximize their profit and followed only their own interests, thus, robbing the state. The image that emerges from these parallel stories is rather frightening even if spectators can only deduce conclusions for themselves regarding some of the phenomena as these remain implicit in the documentary. It was the young victims that paid the price of lack of quality control of supplied material, corrupt hospital management, corruption at the top level of the ministry, corruption among doctors, and indifferent attitude of the staff of public authorities. Indeed, in Romania, anyone who is admitted to one of the units of the health care system suffers from the consequences of these breaches. It is the omnipresent political sphere and businesspeople preying on public procurement and avoiding taxes via offshore operations that run the system. The journalists found out that secret services knew that disinfectants were diluted. It is characteristic that in that period one of the members received a phone call from an officer who advised him that “cornered and idiotic criminals” might be a threat to the personal safety and that of their families if the team went ahead with their investigation. The way one of the politicians tried to capitalize on patients receiving treatment abroad and from the equipment available at one of the hospitals in Bucharest is also a feature that may be seen as typical.

These characteristics take us to the political context of the drama of Colectiv. On the one hand, the perpetual struggle among political parties provides this context as this was the time of the political campaign for the elections that were to be held in December 2016. On the other hand, there is the prolonged struggle for the modernization and „Westernization” of the country against the corrupt post-communist structures and actors that somehow have always managed to persist. This struggle often seems hopeless. Indirectly, the documentary also makes a stand in the debate about the anti-corruption campaign that has been going on since the early 2010s. (Laura Codruța Kövesi, who was then the chief prosecutor of National Anticorruption Directorate and subsequently became the first European Public Prosecutor, even makes an appearance in the film.) The fight against omnipresent corruption has become politicized in the sense of party politics, and many suspects that the prosecutors’ office and secret services are intertwined, thus, that it has become a parallel state. Some even argue that this structure is influenced by foreign influence and that it acts in order to replace the incumbent elite by force. One of the conclusions of the film is that given the lack of means that Romanian society can make use of, there is no alternative to radical solutions. There is no happy ending, and this makes the critique of misfunctioning state institutions even more staggering and also leaves the impression that the situation is hopeless.

The film ends with the parliamentary election of late 2016 that resulted in the return of the Social Democratic Party to power, which meant that the post-communist elite and, specifically, the group that had to resign as a result of the Colectiv scandal came back. The most sensitive scene of Nanau’s documentary is the conversation between the young minister who lost his post to the election and his father. The latter indignantly advises his son that there is no hope and that it would be better if he returned to Vienna where his efforts are appreciated.

The case of Colectiv is not an exception. News reports talk about similar conditions and scandals in the entire region of East Central Europe. The health care system has been in crisis for decades while private hospitals remain fruitful ventures. The system is wasteful and underfinanced at the same time, and reforms did not succeed. These, along with the Westward migration of badly paid medical doctors, nurses and caregivers, the miserable state of most hospitals and the normalcy of „gratuity”, which is, corruption and the contradictory presence of private health care are typical issues in the region. The film Colectiv points out that such institutions and the state are not prepared for an emergency with a large number of victims. The only solution that the minister portrayed in the film could come up with is that people with serious injuries should be treated in Western Europe and Romania would cover part of the costs. This might even be viable in case of singular events but cannot be done in epidemics. The Colectiv becomes the symbol of corruption and irresponsible state behaviour that neglects the common good. The ongoing epidemic lent currency to the issues, thus the channel HBO has recently screened the documentary. It reminds that citizens face structural risks in those countries where the state is not able to run a health care system at an acceptable standard, which would be one of its basic functions.

In an interview, Nanau recently told that the situation had not improved since the accident. In his opinion, as a result of corruption that is present at all levels and that came to light during the investigation that journalists carried out following the fire at Club Colectiv, the series of tragedies continues during the ongoing epidemic.