The Realization and the Pain Occurred Later

Veronika Szeghy-Gayer gave the following interview to bumm.sk in Hungarian language on 3 June 2020.

There were only two days between the declaration of Martin (in Hungarian: Túrócszentmárton) according to which Slovaks would join Czechoslovakia and 28 October 1918, the day on which the creation of Czechoslovakia was declared. Was there a real chance for an independent Slovak state?

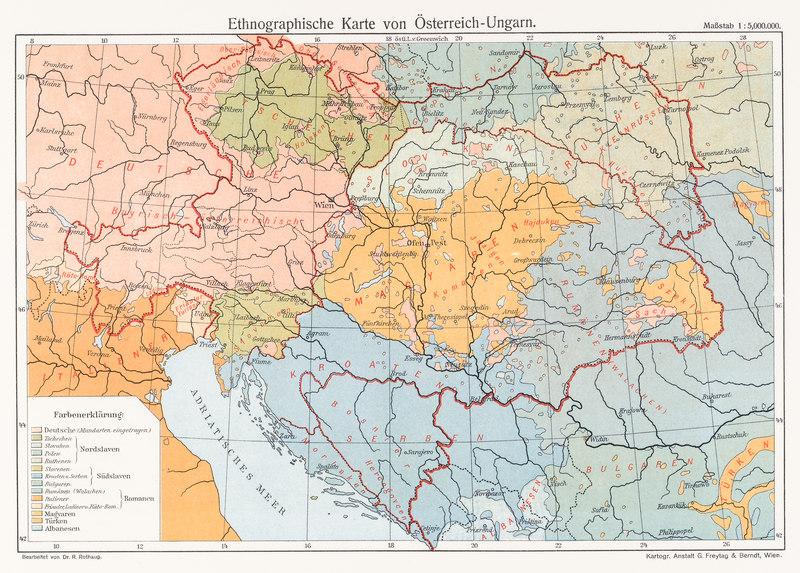

In 1918, it was not a real option. Although a number of Slovak intellectuals imagined their future in an independent national state, there was no chance for gaining international recognition for such a formation. The Slovak elite did not have the kind of a personal network in Western Europe that Czechs could count on. Those Slovak lawyers, bankers, clerical persons, and intellectuals that signed the declaration at Martin agreed that „the branch of the Czechoslovak tribe that had lived in Hungary” shall join the idea of a new Slavic state and should not stay within Hungary. Of course, it is another question of how far the signatories represented Slovak society. There was nobody among them from Zemplén (Zemplín) and Sáros (Šariš) Counties and there were only two people representing Slovaks in Abaúj-Torna (Abov-Turňa). We shall also note that the future status of Slovakia within Czechoslovakia was not yet clear in late 1918. Many Slovaks still hoped that their part would have autonomy as it had been promised to them earlier.

Why was it important for the new Czechoslovak state to include territories with a sizeable Hungarian population within its borders?

Czech politicians soon realized that it is only the Slovaks that may balance out the weight of 3 million Germans that would live in the new state. It is only with the Slovaks that the “Czechoslovak nation” would have a two-thirds majority in the state that they created. Of course, geopolitical strategic and economic concerns also mattered. That is why Csallóköz (in Slovak: Žitný Ostrov) was attached to the area even though the inhabitants of that region were Hungarians.

What kind of military units were there to carry out the annexation of territories that belonged to the Hungarian Kingdom, which was falling apart? How did local inhabitants react?

It was mainly Czech and Slovak troops (legionaries recruited from POW camps to fight against the Central Powers) from the Italian theatre and to some extent from the French theatre that were regrouped and sent with the order to carry out the occupation in late 1918. Slovak volunteers joined them between November 1918 and January 1919. Initially, Italian officers and commanders led these units, but these were replaced by French personnel in the spring of 1919 since Italians were on exceedingly good terms with the local Hungarian population.

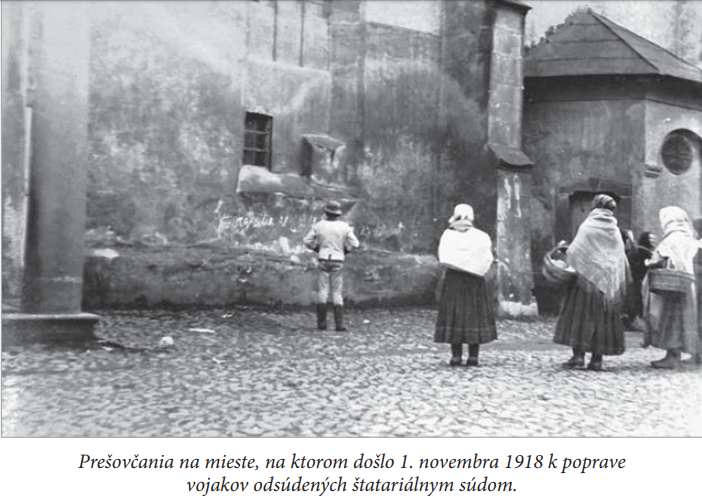

Local communities believed that military occupation would be a temporary phenomenon and leaders of local public administration expected military units to help them to maintain order. Demobilized soldiers of the Hungarian army began to loot in towns and in the countryside from late October 1918 and dissatisfied civilians joined them in large numbers. It was not only public notaries that fell victim to the anger of people but landlords and Jewish merchants, too. At one extreme, the situation started to get out of hand in Eperjes (in Slovak: Presov). The people’s assembly meeting ended up in looting on 31 October. In order to deter others, 41 soldiers and two civilians were executed the very next day at the square between the Catholic and the Lutheran church. Later on, this event entered Slovak public memory as the “mutiny at Presov” and it made other towns realize that they would not be able to handle similarly violent incidents without external help.

The way foreign troops were received depended on the ethnic composition of the population and also on whether there was a local elite that sympathized with the idea of Czechoslovakia. At Érsekújvár, (in Slovak: Nové Zámky) there was armed resistance in early January but soon failed just like similar attempts elsewhere. Budapest did not support these actions and there were not enough people that were ready to take up arms.

And what about Kassa (Kosice)?

Kassa, partly as a result of the action that Miklós Molnár social-democratic commissioner took, avoided bloodshed and looting that Eperjes or other parts of Slovakia experienced. He invited Czechoslovak troops on 29 December 1918. At the same time, he also believed that occupation would be temporary and not definitive. There was considerable hostility towards the new power from both the Hungarian state authorities and the local population. Moreover, several civilians fell victim to the occupation between January 1919 and June 1919. Among these, the firing that followed the demolition of the Honvéd (Hungarian soldiers) statue in March 1919 is quite well-known. Two people died in that incident. Although Kassa has always been on the virtual map in the conscious of Slovaks, there were hardly any Slovak intellectuals in the city that knew the town and could have been nominated to important offices. Vladimír Mutňanský was among the exceptions. He was the first Slovak mayor of the city. Although he was not born in Kassa, he studied law in the town and was socialized in the Hungarian public administration. He also had good relations with the local elite, for example with Endre Puky vice-prefect of Kassa.

Subsequently, Kassa turned into a Slovak town in hardly two decades– at least according to statistics. This was not only the outcome of the Czechoslovak nationalism. Within the framework of the new state, Kassa assumed strategic importance. Governments tried to turn it into a kind of a regional center of Eastern Slovakia that linked the Sub-Carpathian region to the Czech lands. The majority did not have difficulties adjusting to the new situation although, viewed from Prague, Rákóczi’s town had an oppositional outlook. (Notably, Edvard Beneš visited Rákóczi’s tomb in the second half of the 1930s.) At the municipal level elections, Hungarian minority parties won the highest number of votes with the exception of 1932 when the Communist won. Christian Socialism had a strong base among the artisans and workers were also organized.

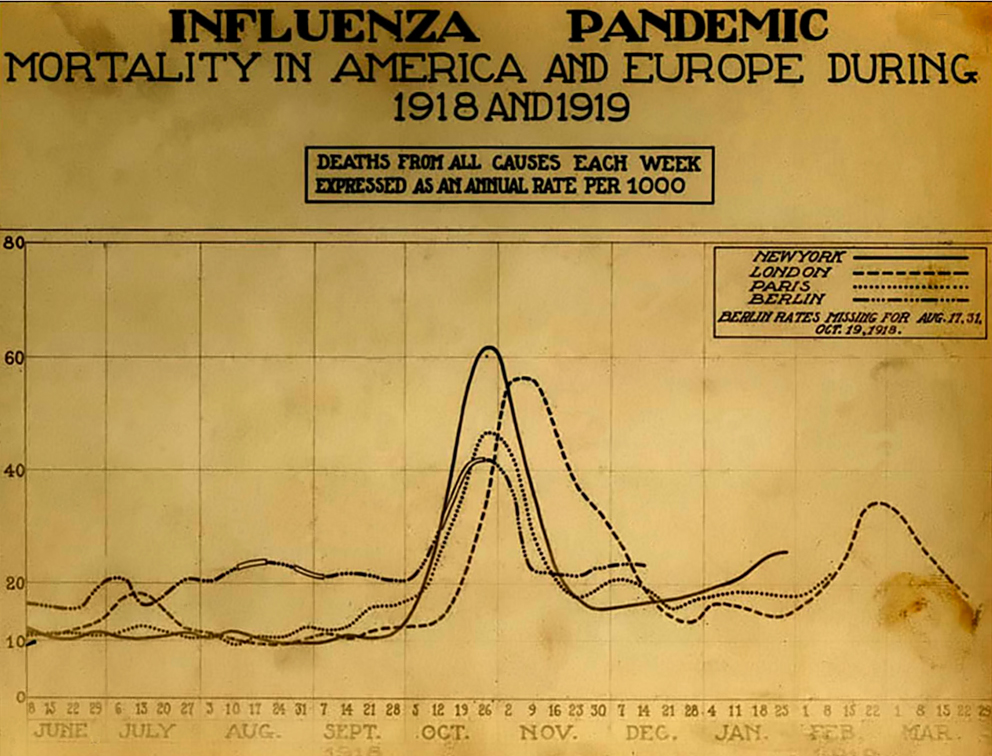

Between 1918 and 1920 there was an invisible enemy that threatened the population: the Spanish flu. Was the disease that mainly attacked young people or the question of state succession that interested people more?

An „everyman” only became conscious of the fact that Czechoslovakia had been created following the military occupation of the region and when the new public administration was in place. In November-December 1918 everyone was waiting for family members to return from the war, while part of the political elite was euphoric about the democratic turn in Hungary. On the other hand, the second wave of the flu hit in the middle of problems of public security and public supplies. Town administrations in the Highland reacted with some delay to the epidemic.

According to some estimates, the Spanish flu killed at least 10 000 people in the territory of present-day Slovakia. About 10% of the population of Pozsony (In Slovak: Bratislava) and Kassa became infected and two-thirds of the victims were below 40 years of age. This feature and the capacity of the virus to kill quickly induced fear in contemporaries. In the last months of 1918, nearly 200 people died of the flu in Kassa alone. In Pozsony, dozens of the deceased were taken to the St Andrew’s cemetery daily. In such circumstances, it might have seemed indifferent that some people declared the creation of a state in Prague that nobody had heard of before. Yet, those that lost their son that had just returned from the war or the person whose shop, his lifetime achievement and investment, was looted or the person that could no call for a medical doctor because medical doctors were still at the front and in a situation where one faced a shortage of flour and coal, even the fact that the thousand-year-old Hungarian state was living its last minutes was of secondary importance. The realization and the pain occurred later on.

International boundaries seemed to solidify after the retreat of the Red Army. What happened to the public servants of the Hungarian state?

From January 1919, representative of the Czechoslovak state began to introduce the new public administration. As part of this, public servants were required to take the oath of loyalty. Understandably, many of them resisted at that time. The strike of February 1919 was the clearest manifestation of this. The majority still believed that the Hungarian state would prevail. The attitude of Budapest triggered doubts, however. They hardly received clear directions about what they should do and if they were expected to start serving under the new state or not. Thus, everyone was left to their own faculties. This is insufficient in a situation when borders keep changing.

The wave of those refugees that refused to take the oath only began in August 1919, after the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Until 1924 more than 100 000 people left the territory of present-day Slovakia and the Sub-Carpathian area. Among these, we do not only find public servants, but also schoolteachers, intellectuals, and military officers. There were those that were removed from their positions, other left out of their own choice and left family homes, social status, achievements behind for an uncertain future. Upon their arrival in Hungary, a large percentage of them had no choice but to stay in railway wagons, temporarily.

What do we know about those public servants and public employees that stayed?

On the one hand, there were those that cooperated with the new power. For example, such high ranking people as the mayors of Rozsnyó (In Slovak: Rožňava), Nyitra (In Slovak: Nitra), Bártfa (In Slovak: Bardejov) or Késmárk (In Slovak: Kežmarok), medical officers and other municipal officeholders. The new state could accommodate them since, in the first period, the Czechoslovak government faced a serious shortage of cadres at all levels of administration.

Regarding former state employees such as teachers, postmen, veterinary doctors, financial officers, there is a different picture. Their life went differently after Trianon. If they spoke the language of the new state and were seen as politically loyal, they could stay in their officers once they took the oath of loyalty. This was more typical in education and in financial institutions. At the police, there was a complete renewal of personnel between 1919 and 1922. At least one-third of the new staff came from the Czech lands. The situation was again different for the 20 000 railways and postal services employees that were dismissed following the strike in February 1919. It was only in 1924 that their status was finally settled based on a law that was ratified four years earlier. For them, the early 1920s were the most difficult. they were forced to find a new occupation and sustained their families in some way. Most of them started receiving a pension in 1924, but there must have been a lot of hurts accumulated in them.